FADE IN:

INT. OFFICE – FILM STUDIO – DAY

A STUDIO EXEC gestures affably as TWO HANDS reach toward one another.

STUDIO EXEC

Story, this is VFX. VFX, this is Story. You two will be working together now, so I want you to get to know each other.

The hands connect and shake. Shimmering light envelops them and radiates in all directions….

“For bigger films, the VFX supervisor now has as much involvement as the director. If you’re a writer planning to use a visual effect, it’s worth it to explore how the effect works. Not only will it help you understand how your idea will manifest but also how you can write to it. Consider researching the technology that tells your story as you would research the circumstances of the story itself.”

[Marc Steinberg – 2024]

When Christopher Nolan completed the script for Oppenheimer, the first person he showed it to was executive producer, Dame Emma Thomas, who is also his wife.

The second person he showed it to was his visual effects supervisor Andrew Jackson. Because Nolan’s first priority was to find ways to show the scientific phenomena Oppenheimer was seeing in his head.

According to Jackson:

“He was imagining things like subatomic particles, but very few of these things had been observed at that time.”

The visual effects team went into rapid deployment mode, creating all kinds of experimental footage.

Per DigitalSpy:

“They developed innovative ways of showing particles, waves, chain reactions, bursting stars, and droplets of molten metal exploding. Nolan passed this footage on to composer Ludwig Göransson. “I saw how they did that splitting of the atoms, with this ultraviolet light,” recalls Göransson. “I was sitting in a dark theater seeing this huge screen and these lights swirling around, and I was like, Okay, this is what I want the music to sound like.”

Later, editor Jennifer Lame would cut some of this footage into the film alongside real world images of droplets, ripples, crackling fires, and breaking glass, to try and depict the way that Oppenheimer, in his own words, was “troubled by visions of a hidden universe.” These inserts, which eventually become more and more ominous, are a key visual motif in the film.”

[Digital Spy, Ian Sandwell, March 11, 2024]

Oppenheimer is not a documentary about scientific phenomena; it’s a narrative film about a man, his struggles, challenges, relationships, and his personal journey. Yet for Nolan, VFX was the first priority for developing the film, and those effects in turn were crucial in determining the music, editing, and other key aspects of the movie.

Nolan is not alone in giving primacy to the technical aspects of filmmaking. In fact, VFX is everywhere.

From the loneliest social media post to the biggest film of the year, you will find VFX. Not to be confused with FX or “visual effects”, VFX is the digital enhancement of footage. Visual effects are on-set or optical enhancements such as latex creatures or rear projection as in early movies.

The demand for VFX in post-production has increased every year since its introduction. It bridges many elements in movie making from the little fixes for continuity or beauty to becoming a virtual character in the story. You can take it a step further and you have a CG movie where the entire film is created within the computer environment.

Whether you are a fan of the CG movies or not, it is worth noting that companies such as Pixar and Dreamworks write their own stories to be animated. They don’t borrow from books like the old Disney films did. This isn’t by accident but more out of necessity as traditional scripts fail to take advantage of what the CG movie can offer. It’s hard to imagine Billy Wilder writing Kung-Fu Panda, but at the same time it’s not hard to imagine Fantastic Voyage as a CG film either. The point is, because the nature of the canvas in a CG film is (only?) near photo-real, then the structure of the story has to favor the action, where CG animations can do things and go places that real world cameras just can’t. In between the nostalgic traditional drama scene in a film and CG films lives VFX.

VFX is not just a tool, it’s a whole bunch of tools, where some will be familiar and some are yet to be discovered. We’ll go over a few of those tools here and discuss how to write to them, but the main thing to keep in mind is that there is a VFX person who can make whatever idea you have in your head happen on film. There’s no reason for you to ever think that your idea couldn’t be produced.

Those who do VFX, do it out of love for it. Those who don’t love doing it will be frustrated by the process and overwhelmed by the meticulous nature of it. It’s the same kind of personality trait you might find in someone who builds a model Clipper ship inside a glass bottle with a pair of tweezers and a knife. They want the challenge.

The most used VFX tools are also some of the oldest. Let’s begin with background replacements or “green screens”. Even the oldest movies took advantage of rear screen projection. Back when, they would place a car in front of a movie screen and project footage of driving down a street from behind the screen. The camera in front of the car that is recording the scene as it will be seen in the cut of the movie is recording the car and the actors in it, with the footage of the street moving behind them. The end result is, everyone appears to be driving while all the actors and crew are perfectly safe, not moving, because they’re inside a sound stage. This allows actors to act without having to concentrate on driving, or to jump around the car without risk of injury and so on.

To help sell the effect, they would shake the car as if it were on the road and add fans to simulate the wind from driving a convertible.

There are limitations of course. You can’t move the camera with rear projection or you lose the illusion. Whenever the rear projection footage would go around a turn, the actors would have to pretend to turn the car in sync with the footage which never really worked quite right because the brain knows it should be seeing parallax and the correct physics for everything. So, the idea was evolved as technology allowed.

Instead of using projectors VFX borrowed from the meteorologists. TV news needed a way for the weatherman to stand in front of changing weather maps as he delivered the forecast. The answer they came up with was the blue screen, not green, not yet. It was discovered that if you split color video into 3 channels, red, green and blue then you could manipulate those channels in a way that would give you white where there was blue and black everywhere else. Once you have a black and white matte then you can introduce something new into the white and preserve what’s in the black, and just like that you can put in a new whether map on the fly for your weatherman at the click of a button. It turns out that green is a better color than blue because when you separate color channels, the green is a much stronger channel with better information than the blue.

Today we just use whatever color is foreign to the subject in front of it. If you put green ivy on a green screen, it doesn’t work but if you use a blue screen behind ivy, it will. So, weathermen couldn’t wear blue, or they would become part of the map they were pointing at.

Film people saw that and developed it even further. Through the late 60’s to the 1990’s we have blue and green screen footage in lots of movies. Green screens are still used today all the time, but now VFX can clean them up perfectly and make it very difficult to tell whether the actor is really at the location in the story or not. Some films are completely shot on green screen such as “300” and “Avatar”. For a writer who is envisioning a place that doesn’t exist, the green screen is your friend. Your story can take place anywhere at any time given the budget.

And green screens are not just for actors. Model builders would place their spaceships in front of a green screen and shoot it adding the stars and explosions as another layer. 2001: A Space Odyssey had really perfected this technique under Douglas Trumbull where multiple passes were filmed using the exact same camera movement to get more and more realism out of it. One pass for beauty, one pass for actors, one pass for stars, on and on. This was utilized again in Blade Runner and in Star Wars, and these films opened the doors for all the effects to come.

Another favorite VFX is the split screen. Whenever an actor needs to appear twice in frame, VFX provides the split screen. Where the left half the screen is shot at one time and the right half is shot at another time, allowing one actor to portray his twin or a clone or his doppelgänger as the case might be. This effect was common on shows that had double roles for actors, such as I Dream of Jeannie and Back to the Future. There were limitations here too of course. Again, they couldn’t move the camera as half the screen would be moving in a different direction than the other half. But today with digital compositing we can track each side and keep the two sides moving together perfectly.

And it doesn’t have to stop at 2 halves being split.

With computers we can split the screen 100 times. Make a 99-day advent calendar with something different in each window that goes on for 90 minutes. Little by little films are experimenting with this very idea where the entire movie takes place on a computer’s desktop or within a smart phone. Essentially a bunch of little movies all stitched together one over the other.

By now you may be realizing that with VFX the idea isn’t to show something but rather to hide it all. If VFX is doing its job, then the audience never knew it was there.

VFX’s main priority is to keep the audience in the story. If there’s a failed effect anywhere in the movie, then the audience is awakened from the illusion and you’ve lost them. Movies with bad effects are only of interest to those who love movies already and love looking behind the curtain. The only place for a bad effect is in a movie about bad effects. However, good effects still cost a lot of money and bad effects are cheap. Such is the world.

It is worth considering what amount of VFX budget you want to write for. Even if you don’t think your film will need VFX, it will. Production will always want some help to cover up a crew member or hide a production light or fix the little things the camera sees that are missed in the frenzy that occurs on the word “action”.

Green screens and split screens have been around long enough to where they are pretty cheap to work with as long as they are shot properly and with forethought. The common phrase, “we’ll fix it in post” is just another way of saying “we’ll spend a lot of money later”.

For bigger films the VFX supervisor has as much involvement as the director now. Planning out how the effect works is as effective as putting money in a savings account. As a writer, if you plan on using a certain effect, it’s well worth it to explore how that effect works. Not only will it help you understand how your idea will manifest, but it will also tell you how to write to it. Meaning if you’re writing a story about a character who learns to manipulate fire, you’ll want to start small and go through the evolution of the effect as the character does. Little fires to start and big ones for the ending while using the strength of the effect in between. Consider researching the technology that tells your story as you would research the circumstances of the story itself.

And now here we are. There have been countless steps since the first time someone put a map of a tropical storm in front of a green screen. Countless steps from the giant tentacles of 1,000 Leagues Under the Sea to the aquatic Na’vi of The Way of Water. And today we are taking on bigger challenges than ever.

VFX. State of the Art. Early 2020s.

In James Cameron’s first Avatar sequel, characters often remain underwater for long action sequences. A few years ago, these kinds of scenes would have been rejected because they were too difficult and complex to film. Water distorts light which makes it nearly impossible to get clear shots, and actors would be constantly popping back up to the surface to catch their breaths. Most likely the writer would have been sent back to reimagine the story and return with a draft that was shootable.

However…

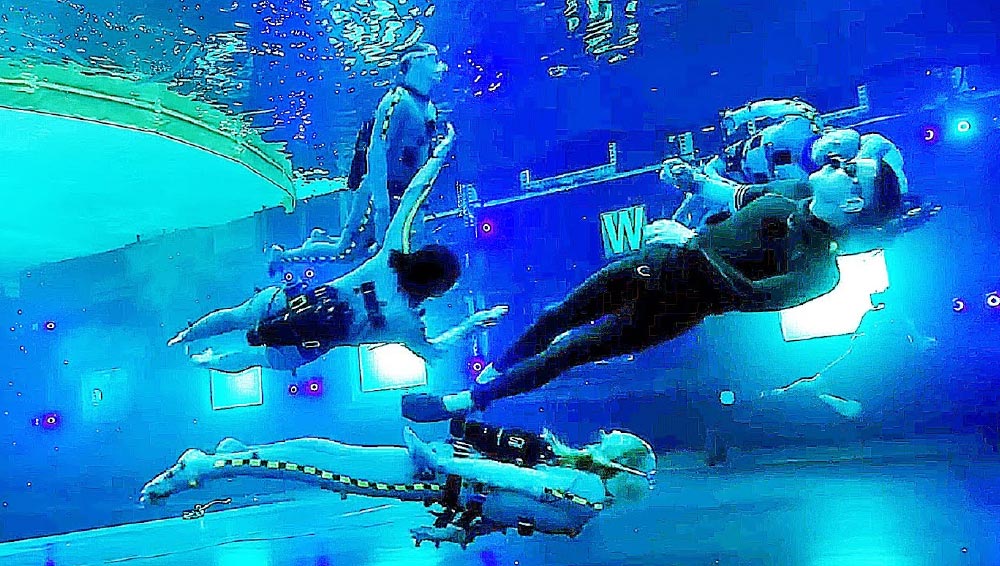

The Way of Water pioneered new techniques for its 2,225 water shots. They allowed effective shooting both underwater and at the surface. The digital techniques worked by breaking the distinctive qualities of water into separate processes including aerations, splashes, droplets, waves, sprays, and mists. This technology combined with the innovative use of ultra-blue light underwater and infra-red at the water’s surface gave a clarity to the water shots never before achieved.

The technical components then had to interface with the live actors. How would they perform their long underwater action scenes? Scuba gear could have been used, but that creates bubbles, and bubbles ruin underwater shots. To work around this, the actors were put through six months of intense training in diaphragmatic breathing which increased their lung capacity so they could hold their breaths for five minutes at a time. They were then able to stay submerged long enough to carry out the film’s astonishing subaquatic action scenes – with no bubbles.

These effects were insanely complex and none of it was necessary. The filmmakers could have simplified the story and shot around the bubbles with standard underwater cameras using natural light. They’d have still had a movie – but it would have been so much less. As The Way of Water’s senior animation supervisor Daniel Barret put it, “Where you really sell it is in those tiny little details”.

In this case the tiny details produced a film with the third highest box office of all time. And an academy award for best special effects.

Unfortunately, most of us are not in a position to hire a staff of VFX sorcerers and send them off to invent nearly impossible effects while training actors to do nearly impossible stunts. There’s only one James Cameron. For the rest of, studying the VFX that are available, and learning which ones can be accomplished within the budgets we have, is a great first step. Actually understanding how they work is also a good thing. The more you know, the better. And that technical knowledge might ultimately help you cross-over from writer to writer-director. It’s a lot more work but is also gives you a lot more control over your story. As a hyphenate, you’ll get more credit if your project succeeds. And all the blame if it fails. Life is cruel. But movies are glorious. And understanding VFX may be the “power up” that keeps you in the game.